In On learning InnoDB: A journey to the core, I introduced the innodb_diagrams project to document the InnoDB internals, which provides the diagrams used in this post. (Note that each image below is linked to a higher resolution version of the same image.)

The basic structure of the space and each page was described in The basics of InnoDB space file layout, so now we’ll expand on that to describe InnoDB’s structures related to management of pages and extents, and “free space” management, and how it tracks pages allocated to the many different purposes for which pages are used.

Extents and extent descriptors

As described previously, InnoDB pages are normally 16 KiB, and are grouped into 1 MiB blocks of 64 contiguous pages, which is called an “extent”. InnoDB allocates FSP_HDR and XDES pages at fixed locations within the space, to keep track of which extents are in use, and which pages within each extent are in use. These pages have a pretty simple structure:

They contain the usual FIL header and trailer, an FSP header (discussed a bit later), and 256 “extent descriptors” or just “descriptors”. They also contain a sizable amount of unused space.

Extent descriptors have the following structure:

The purpose of the various fields in an extent descriptor are:

- File Segment ID: The ID of the file segment to which the extent belongs, if it belongs to a file segment.

- List node for XDES list: Pointers to previous and next extents in a doubly-linked extent descriptor list.

- State: The current state of the extent, for which only four values are currently defined: FREE, FREE_FRAG, and FULL_FRAG, meaning this extent belongs to the space’s list with the same name; and FSEG, meaning this extent belongs to the file segment with the ID stored in the File Segment ID field. (More on these lists below.)

- Page State Bitmap: A bitmap of 2 bits per page in the extent (64 x 2 = 128 bits, or 16 bytes). The first bit indicates whether the page is free. The second bit is reserved to indicate whether the page is clean (has no un-flushed data), but this bit is currently unused and is always set to 1.

Other structures that reference an extent do so using a combination of the page number of the FSP_HDR or XDES page in which the extent’s descriptor resides, and the byte offset within that page of the descriptor entry itself. For example, the extent referenced by “page 0 offset 150” is the first extent in the space, accounting for pages 0-63, while “page 16384 offset 270” accounts for pages 16576-16639.

List base nodes and list nodes

Lists (or “free lists” as InnoDB calls them) are a fairly generic structure that allows linking multiple related structures together. It consists of two complementary structures, which form a nicely featured on-disk doubly-linked list. The “list base node” has the following structure:

The base node is stored only once in some high level structure (such as the FSP header). It contains the length of the list, and pointers to the first and last list node in the list. The actual “list nodes” look very similar:

Instead of storing first and last pointers, of course, the list node stores previous and next pointers.

All pointers consist of a page number (which is required to be within the same space), and a byte offset within that page where the list node can be found. All pointers point to the beginning (that is, N+0) of the list node, not necessarily of the structure being linked together. For example, when extent descriptor entries are linked in a list, since the list node is at offset 8 within the XDES entry structure, the code reading a list entry must “know” that the descriptor structure starts 8 bytes before the offset of the list node, and read the structure from there. (It would’ve perhaps been a good idea to ensure that the list node is always first in any structure, but that is not the case.)

The file space header and extent lists

Aside from storing the extent descriptor entries themselves, the FSP_HDR page (which is always page 0 in a space) also stores the FSP header, which contains a lot of lists, so couldn’t easily be described earlier. The structure of the FSP header is as follows:

The purposes of the non-list related fields in an FSP header are (not in order):

- Space ID: The space ID of the current space.

- Highest page number in the space (size): The “size” is the highest valid page number, and is incremented when the file is grown. However, not all of these pages are initialized (some may be zero-filled), as extending a space is a multi-step process.

- Highest page number initialized (free limit): The “free limit” is the highest page number for which the FIL header has been initialized, storing the page number in the page itself, amongst other things. The free limit will always be less than or equal to the size.

- Flags: Storage of flags related to the space.

- Next Unused Segment ID: The file segment ID that will be used for the next allocated file segment. (This is essentially an auto-increment integer.)

- Number of pages used in the FREE_FRAG list: This is stored as an optimization to be able to quickly calculate the number of free pages in the FREE_FRAG list, without iterating through all extents in the list and summing the free pages available in each.

List base nodes for the following extent descriptor lists are also stored in the FSP header:

- FREE_FRAG: Extents with free pages remaining that are allocated to be used in “fragments”, having individual pages allocated to different purposes rather than allocating the entire extent. For example, every extent with an FSP_HDR or XDES page will be placed on the FREE_FRAG list so that the remaining free pages in the extent can be allocated for other uses.

- FULL_FRAG: Exactly like FREE_FRAG but for extents with no free pages remaining. Extents are moved from FREE_FRAG to FULL_FRAG when they become full, and moved back to FREE_FRAG if a page is released so that they are no longer full.

- FREE: Extents that are completely unused and available to be allocated in whole to some purpose. A FREE extent could be allocated to a file segment (and placed on the appropriate INODE list), or moved to the FREE_FRAG list for individual page use.

File segments and inodes

File segments and inodes are perhaps where InnoDB terminology and documentation are murkiest. InnoDB overloads the term “inode”, which is in common use in filesystems, and uses it for both INODE entries (a single small structure) and INODE pages (a page type holding many INODE entries). Ignoring the naming confusion for a moment, an INODE entry in InnoDB merely describes a file segment (frequently called an FSEG), and will be referred to as a “file segment INODE” from now on. The INODE pages that contain them have the following structure:

Each INODE page contains 85 file segment INODE entries (for a 16 KiB page), each of which are 192 bytes. In addition, they contain a list node which is used in the following lists of INODE pages in the FSP_HDR‘s FSP header structure as described above:

- FREE_INODES: A list of INODE pages which have at least one free file segment INODE entry.

- FULL_INODES: A list of INODE pages which have zero free file segment INODE entries. When using “file per table” spaces, this list in each per-table space will be empty unless the table has more than 42 indexes, as each index consumes exactly two file segment INODE entries.

A file segment INODE entry has the following structure:

The purpose of each of the non-list fields in each INODE entry are:

- File Segment ID: The ID of the file segment (FSEG) described by this file segment INODE entry. If the ID is 0, the entry is unused.

- Magic Number: The value 97937874 is stored as a marker that this file segment INODE entry has been properly initialized.

- Number of used pages in the NOT_FULL list: Exactly like the space’s FREE_FRAG list (in the FSP header), this field stores the number of pages used in the NOT_FULL list as an optimization to be able to quickly calculate the number of free pages in the list without iterating through all extents in the list.

- Fragment Array: An array of 32 page numbers of pages allocated individually from extents in the space’s FREE_FRAG or FULL_FRAG list of “fragment” extents. Once this array becomes full, only full extents can be allocated to the file segment.

As a table grows it will allocate individual pages in each file segment until the fragment array becomes full, and then switch to allocating 1 extent at a time, and eventually to allocating 4 extents at a time.

List base nodes of extent descriptors are also present in each file segment INODE entry:

- FREE: Extents that are completely unused and are allocated to this file segment.

- NOT_FULL: Extents with at least one used page allocated to this file segment. When the last free page is used, the extent is moved to the FULL list.

- FULL: Extents with no free pages allocated to this file segment. If a page becomes free, the extent is moved to the NOT_FULL list.

If the last used page is freed from an extent in the NOT_FULL list, the extent could be moved to the file segment’s FREE list, but in practice is actually moved directly back to the space’s FREE list instead.

How indexes use file segments

Although INDEX pages haven’t been described yet, one small aspect can be looked at now. The root page of each index’s FSEG header contains pointers to the file segment INODE entries which describe the file segments used by the index. Each index uses one file segment for leaf pages and one for non-leaf (internal) pages. This information is stored in the FSEG header structure (in the INDEX page):

The space IDs present are somewhat superfluous — they will always be the same as the current space. The page number and offset point to a file segment INODE entry in an INODE page. Both file segments will always be present, even though they may be completely empty.

For example in a newly created table, the only page that exists will be the root page, which is also a leaf page, but is present in the “internal” file segment (so that it doesn’t have to be moved later). The “leaf” file segment INODE lists and fragment array will all be empty. The “internal” file segment INODE lists will all be empty, and the single root page will be in the fragment array.

Tying it all together

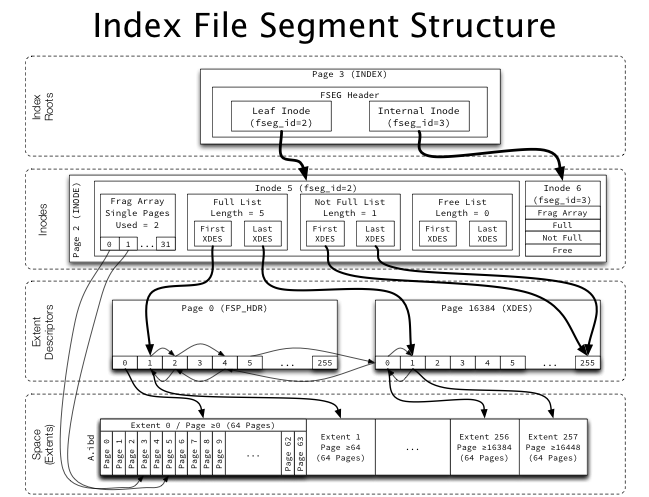

The following diagram attempts to illustrate the entire multi-level structure for an index:

The index root page points to two inodes (file segments), each of which have a fragment array (pointing to up to 32 individual pages from a fragment list), as well as several lists of whole extents, which are linked together using list pointers in the extent descriptors. The extent descriptors are used both to reference an extent as well as to keep track of free pages within an extent. Easy!

What’s next?

Next we’ll look at the structure of one of the most important page types from a user’s perspective, INDEX pages. We’ll then look at how InnoDB structures its indexes at a high level.